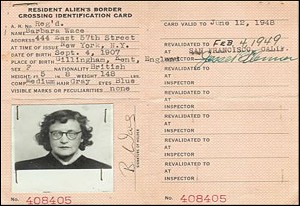

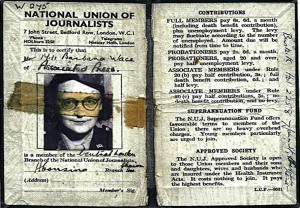

The voyage back to England, 1940 – by Barbara Wace

Written by Barbara in April 1995:

Leaving for England in 1940 was a rather lonely business, for you were not supposed to say when the convoy was leaving – and so nobody could see you off. I had sent my heavy trunk from San Francisco in the aircraft carrier Attacker. The captain was a friend of mine, and the vessel was built in the San Francisco area. It was some time – months in fact – before the Attacker reached Britain, and my baggage turned up in London. The Attacker saw service on the way home, and so did my trunk. Also with them was Scott Newhall – later editor of The San Francisco Chronicle – who they took with them as a war correspondent. He was properly accredited with the U.S. Army, but until the Attacker sailed no outfit had agreed to take him because he had lost a leg in an accident when he was younger.

I think there were about fifteen passengers in my ship in the convoy. It had been a banana boat and on its deck were fastened two locomotives and two tenders which, it was rumoured, were needed for somewhere on the continent – not for British Rail which, apparently, had a narrower gauge. Having those huge vehicles strapped to the deck made the ship very top heavy, as there was nothing much in the holds to act as ballast. When the sea got rough, which it did a few days into our journey, we rolled terrifyingly and, a few days out, in mid Atlantic we had to heave to and let the main convoy go on without us except for a loyal little escort of two corvettes and one destroyer. At the time I was, at first, too seasick to care or even notice.

The passengers divided quite naturally into two groups for socialising in the two public rooms. My cabin companion was a very gentle and genteel ex-ladies maid to a rich New York lady. She had been in service all her life since she emigrated to teh U.S. and had led a totally sheltered life. I really admired her for volunteering under the scheme as nobody expected her to, and I wonder how she got on, not only because of the bombs, but because of the totally different life she must have had to live after the comfortable, select world of New York’s upper domestic servants. We got on well in the cabin once we stopped being seasick but, except in the dining saloon, our groups seldom overlapped.

The leader of my group was an American economist, Charles P Kindleberger, who I met as I walked up the gangway, and who has remained a close friend since. A professor at M.I.T., he had the rank of Captain and was on his way to join the secret group of experts who decoded enemy codes and created codes for us at ——-. Another leading member was a Dutchman, whose name was something like Boreel. He was charming and extremely good looking and a bit of a mystery. He had been travelling, we gathered, somewhere in the far east. With him was a sophisticated Frenchman whose name I forget. He worked in the dress trade and was obviously high up, well heeled and very Parisian. I met him again during the War in London and remember him as very good company on the voyage. Out last group member was a Geordie, in his twenties, who had obviously worked in the docks in the north. We got on very well with him though sometimes we could not understand his very thick accent. And we did wonder why he came on board in handcuffs under police escort and left the same way. He was a good companion and we were sorry to see him marched away. We never of course asked him why he was under arrest.

I am not sure where we sailed in the Atlantic but I was relieved to find that seasickness does finally pass.

Assembled in our little public room, gossiping away, we had a congenial time, broken on the third day out, in the middle of the huge convoy by a rather frightening bang. Everybody except me rushed out on deck to see what it was. I was so frightened I froze to my seat. When the Captain came in he congratulated me on being the only one to keep my head. If only he knew I was so frozen with fear I could not have moved even to save my life. When I am frightened I cannot move.

After, I think, about ten days in what seemed like mid Atlantic the weather got even worse, though by that time most of us had got our sea legs okay. But the huge waves and our top heavy cargo made the ship lurch from side to side and felt like we would turn at any moment. This is when the convoy went on without us and, I think, we were there in mid-ocean with our little escort for about four days, finally moving on alone until, after days, we passed the Irish coast, and then, at last somebody said it was Liverpool ahead – and home.

The next few days, anchored outside Liverpool Harbour and in radio contact with the U.K. were, I think, the most frustrating of my whole life. There was England and there were we just nearby – and we were not allowed to land. I was never quite sure why we were held up, but I gathered it had something to do with the fact that the charming Dutchman was an unknown quantity, that nobody knew what he had been doing in the far East and that at that moment in Liverpool there was no official available who was capable of interviewing and clearing him. I believe there was difficulty too in getting our Geordie transferred to prison or wherever he was expected. Anyway, when we were finally disembarked at Liverpool we got the impression they were very busy indeed in that city – though they did give us a lovely hot welcoming tea in the Adelphi Hotel – at least the W.V.S did, and that was the first time I enjoyed the benefits of that wonderful wartime organization. It was two full days before we were allowed to disembark.