His Savage Eyes

by Rebecca Lori:

Over time humanity has forged a powerful relationship with its surrounding landscape. So much so, that one is almost forced to question one’s existence when faced with an ocean filled with inky black waters or an open canyon where the depth defies perspective. There is something irrefutably quieting in the scale of the natural world – man looks at the stars in the sky, the vast open spaces in the desert and almost at once he feels small.

When looking at the history of photography, and in particular landscape photography, there have been a number of approaches that have challenged the way in which we see the world. The likes of Ansel Adams determined to capture the open spaces of America in perfect (and often criticised) detail, while other photographers such as Josef Koudelka, in his reportage, chose instead to challenge our vision with noticeably broader brush strokes.

When looking at the history of photography, and in particular landscape photography, there have been a number of approaches that have challenged the way in which we see the world. The likes of Ansel Adams determined to capture the open spaces of America in perfect (and often criticised) detail, while other photographers such as Josef Koudelka, in his reportage, chose instead to challenge our vision with noticeably broader brush strokes.

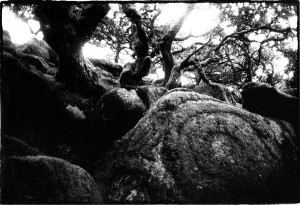

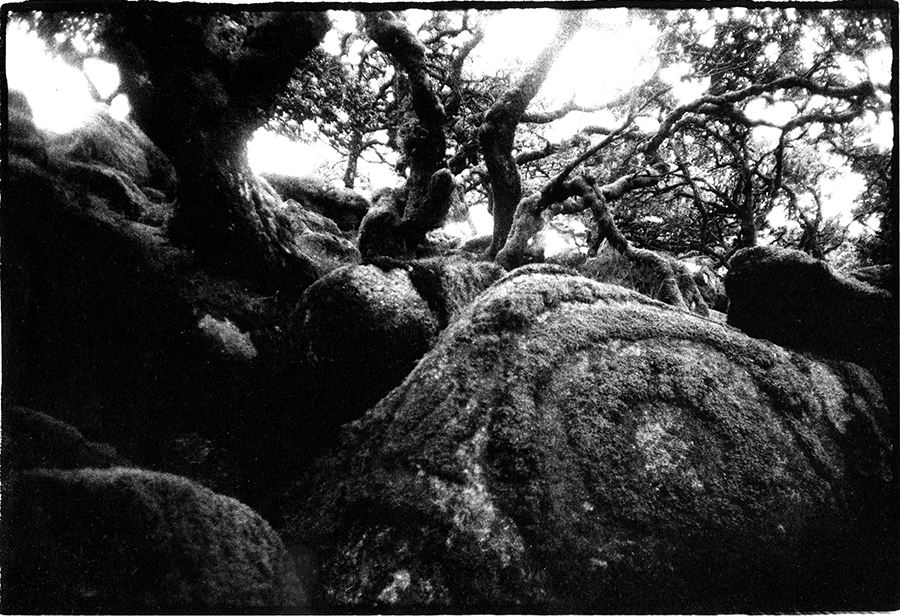

It was once said that Josef’s eye was “savage” and it could be argued that Toby Deveson’s ‘eye’ also shares the same vision – a glance at his work can reveal harsh terrains dominated by shadows and darkness, leading the unsuspecting viewers through mystical landscapes, framed like theatre sets. Gnarly trees give way to sparkling waters, rolling hills overpowered by tempestuous skies; Deveson’s work is simmering with drama and intensity.

Taking inspiration from classic landscape photography, he frames each shot within the camera, relying purely on the geometry of the natural world. Somewhat perversely Deveson chooses to challenge himself in ways modern photographers take for granted…“I restrict myself and give myself boundaries in order to challenge and push my limits”. Therefore, one could ask – does he also restrict the viewer or does he open their eyes to his vision?

Deveson’s work exudes solitude and isolation but paradoxically, often a sense of light, of hope. Could this be the message he is trying to convey? That one cannot exist without the other?

He successfully captures the full range of emotions in the landscape with a fleeting moment, encapsulated indefinitely within the frame. Thus bringing to life a memory, a snatched shutter flash which only the photographer at that moment could see. A mere moment experienced by Deveson is instantaneously transformed for the viewer, allowing them to create their own narrative, despite the fact the moment has indeed, passed. “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.” (Heraclitus) – a sensation all too palpable within Deveson’s frames.

Despite both sharing a deep passion for landscapes, Deveson’s relationship with Ansel Adams isn’t simple. Whilst he can appreciate the undoubted beauty found in Adams’ work, he mourns the loss of the soul within the images. To find this, Deveson turns to, amongst others, Mario Giacomelli. It could be said that he is the antithesis of Adams, carelessly, and perhaps aggressively, creating his work, the focus steering away from a meticulous, technical process and more toward a soulful outcome.

The difference being that Deveson’s work appears to contain both approaches. He spends countless hours in the darkroom, perfecting his prints until the mood of the landscape takes form and evolves in the blood red light, a chemical metamorphosis if you will. The chosen negative, that fleeting moment transformed into a piece of theatre, a dance of light and shadow caught indefinitely on paper.

Roland Barthes sums it up perfectly:

“Photography is a kind of primitive theatre, a kind of Tableau Vivant, a figuration of the motionless and made-up face beneath which we see the dead.” (Camera Lucida)

Alert to the detail in his work, Deveson wants to play with the viewer, to take them away from the expected to the unexpected. This is a darker world where the grass quivers with the wind beneath the charcoal olive groves of Italy, or the waters speak of gentle movement before leading you violently to the rocks. Night and day is often unclear. The visual clues usually found in colour imagery are less apparent in the grey and black tones, bringing the viewer into a world that we are more often than not blind to see.

Barthes would also argue that in order to truly see an image one should close their eyes and, as with Deveson’s work, it need not be rushed.

To simply look at an image is a truly sad prospect, but to really see an image is a blessing and Toby Deveson’s work forces the viewer to widen their vision and see the world through his savage eyes.