Barbara Wace: An obituary

BORN 4TH SEPTEMBER 1907, DIED 16TH JANUARY2003

Kindly provided by Valentine Fallan, with thanks to James Buchan & Anne Sebba

Barbara Wace, the pioneering World War II reporter and international freelancer, has died peacefully at the age of 95 at Morden College residential home in Blackheath, London. Her funeral service is at 11 a.m. on Monday 27 January, at St. Bride’s Church, Fleet Street.

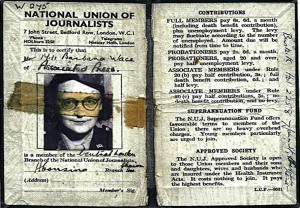

Her last birthday party was also celebration of 65 years of non-stop work in the media as a PR, columnist, feature writer, news broadcaster and press photographer.

Barbara’s world centred on journalism and she never fully retired. She was a resident of Fleet Street from the Blitz years until 1985 – long after the newspapers had left – and was given the Freedom of the City of London. Regularly remembered as Britain’s first woman war reporter at the 1944 Normandy landings (recently: Guardian, G2, 14 November 2001) Barbara’s foreign service experiences and highly-placed contacts enabled her to write incisive post-Empire political comment, still pertinent today. At the height of the Suez crisis, during the build-up of nuclear weapons worldwide, she warned of the consequences of key politicians’ exhausting travel schedules and impossible workloads. ‘Living on the edge of the precipice as we do, one false word, one loss of temper through overstrain, could throw us over the edge into the Third World War’, she wrote in her column for The Daily Sketch (26 November, 1956). ‘The whole future of our nation depends on the wise judgements of overworked ministers and their advisors who, confronted by a sudden increase in highly individual and independent nations, are faced with decisions that can neither be delegated nor left to British diplomats abroad’.

Barbara’s world centred on journalism and she never fully retired. She was a resident of Fleet Street from the Blitz years until 1985 – long after the newspapers had left – and was given the Freedom of the City of London. Regularly remembered as Britain’s first woman war reporter at the 1944 Normandy landings (recently: Guardian, G2, 14 November 2001) Barbara’s foreign service experiences and highly-placed contacts enabled her to write incisive post-Empire political comment, still pertinent today. At the height of the Suez crisis, during the build-up of nuclear weapons worldwide, she warned of the consequences of key politicians’ exhausting travel schedules and impossible workloads. ‘Living on the edge of the precipice as we do, one false word, one loss of temper through overstrain, could throw us over the edge into the Third World War’, she wrote in her column for The Daily Sketch (26 November, 1956). ‘The whole future of our nation depends on the wise judgements of overworked ministers and their advisors who, confronted by a sudden increase in highly individual and independent nations, are faced with decisions that can neither be delegated nor left to British diplomats abroad’.

In her late 80s she was still writing from Outer Mongolia, Ladakh, Greenland, an ice-bound ship en route to Leningrad, the Trans-Siberian railway or Ghana. When no longer able to travel independently, she was giving press interviews about her opinions of war and continuing her long tradition of supporting younger writers’ enterprises. Her advice to new freelancers (Journalists’ Week 10 August 1990) emphasised in-depth research before departure, exclusivity, and finding local people with interesting stories to tell rather than filing routine tourist-oriented reports. Most important, she wrote, was to ‘throw away your prejudices’.

Towards the end of her life, Barbara spoke out against the promotion of war as ‘family entertainment’ in the heritage industry’ Millennium re-enactments. In a local newspaper interview (Greenwich Mercury, 20 Sept 2000) on her 93rd birthday, she said, ‘War is the last resort. It’s a sign of failure – and there are no winners. There should be continual talks between influential people to find ways of preventing wars. The legacy is centuries of debate about the rights and wrongs.’ She lived long enough to know that history really does repeat itself.

Her last television appearance was in mid-2002 for the Australian ‘This Is Your Life’ (Channel 9) for her former colleague and close friend Anne Deveson, the British-born broadcaster, author and human rights activist.

Barbara, who said she never had time to write her memoirs, left a unique cultural legacy. In her 90th year, intrigued by a personal example of historical synchronicity, she sponsored a project set up by former colleagues to restore to the English canon the work of her 12th Century counterpart and possible ancestor, the proto-journalist ‘Master’ Wace, whose controversial verse chronicle of the 1066 Norman invasion of England, Roman de Rou, was translated in full for the first time last year.

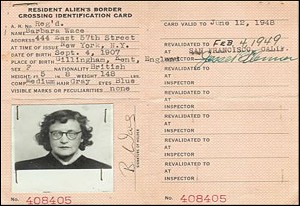

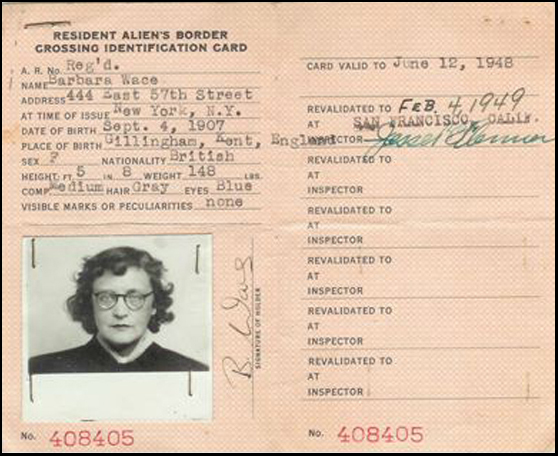

Barbara’s style of trail-blazing journalism reflected her atypical childhood. Born in Gillingham, Kent near Chatham dockyard, she was the second daughter (third child of four) of Eva Sim and Brigadier-General E. Gurth Wace, C.B., D.S.O. previously stationed in India with the Royal Engineers, a World War I veteran and staff officer in France and Flanders. She attended the Royal School, Bath, for the daughters of military officers. A formative experience in the 1920s was living in Europe’s most-disputed borderland when her father was appointed President of the Saar Boundary Commission as representative of the British Empire. His family included Henry Wace, an assistant editor and leader writer for The Times, later Dean of Canterbury Cathedral, and Alan Wace, the eminent Mycenae archaeologist.

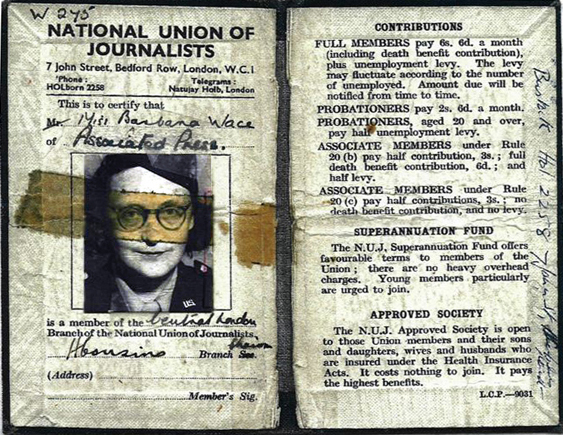

In the 1930s she worked for Colonial Secretary Lord Cranbourne, attending a League of Nations Assembly with the then Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden and, posted to the British Embassy in Berlin, witnessing the many Nazi rallies. She was in the Embassy box at the 1936 Olympic Games, where she watched Hitler’s reaction as the Black American sprinter Jessie Owens won the 100 yards. Back in London, she became Press Officer for the Savoy Hotel. At the outbreak of war she re-joined the Foreign Office and was posted to Washington, New York and San Francisco where she helped to set up the British Information Service – part of the war effort to win U.S. support. Concerned about her family and friends at home, in 1943 she applied to return, signing the required statement that she would take any civilian job she was ordered to do. However, because of her background, Barbara, now 36, was permitted to join the U.S. agency Associated Press, at first writing on Londoners’ reactions to the Blitz.

In the 1930s she worked for Colonial Secretary Lord Cranbourne, attending a League of Nations Assembly with the then Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden and, posted to the British Embassy in Berlin, witnessing the many Nazi rallies. She was in the Embassy box at the 1936 Olympic Games, where she watched Hitler’s reaction as the Black American sprinter Jessie Owens won the 100 yards. Back in London, she became Press Officer for the Savoy Hotel. At the outbreak of war she re-joined the Foreign Office and was posted to Washington, New York and San Francisco where she helped to set up the British Information Service – part of the war effort to win U.S. support. Concerned about her family and friends at home, in 1943 she applied to return, signing the required statement that she would take any civilian job she was ordered to do. However, because of her background, Barbara, now 36, was permitted to join the U.S. agency Associated Press, at first writing on Londoners’ reactions to the Blitz.

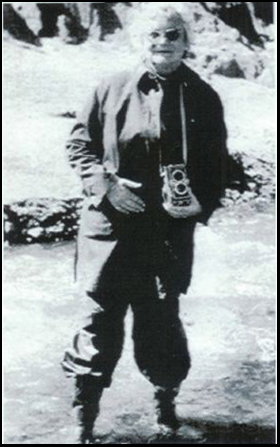

She remarked on the irony that, despite her work in a battle zone, when 550-plus war correspondents were accredited by the British, the job was considered unsuitable for a woman. By chance, she became the first to follow the D-Day landings, working however under American orders and in American army uniform, complete with gas-proof underwear.

The Associated Press had sent a reporter to London to accompany 30 U.S. non-combatant servicewomen (WAACs) to Normandy. But when the call came in July, 1944, she was out. Said Barbara, ‘I was next on the list. I collected my kit at the quartermaster’s at 11.20 that night and by two in the morning was on the way to Omaha Beach in a troop ship.’

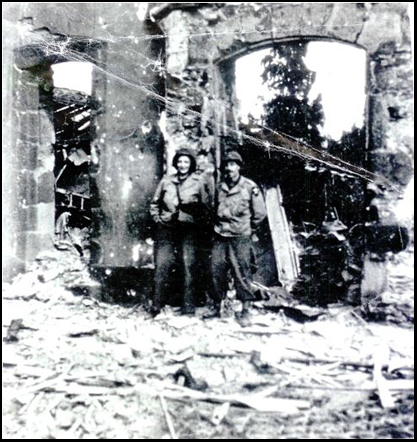

Despite a cable from the bureau chief: ‘Keep out of danger spots. That is an order’, Barbara dutifully filed her reports on the women’s work in Normandy then, characteristically, attached herself to a frontline correspondent for Life Magazine. In September she was on her way to report on the liberation of Paris when the bureau chief diverted her to the massive U-boat base in Brest, Western Brittany. ‘There was no-one else to send,’ she said. The German garrison of 38,000 was holding the base and village and surrendered after a 46-day siege by around 80,000 U.S. troops. The story, however, appeared under a male colleague’s by-line.

Despite a cable from the bureau chief: ‘Keep out of danger spots. That is an order’, Barbara dutifully filed her reports on the women’s work in Normandy then, characteristically, attached herself to a frontline correspondent for Life Magazine. In September she was on her way to report on the liberation of Paris when the bureau chief diverted her to the massive U-boat base in Brest, Western Brittany. ‘There was no-one else to send,’ she said. The German garrison of 38,000 was holding the base and village and surrendered after a 46-day siege by around 80,000 U.S. troops. The story, however, appeared under a male colleague’s by-line.

She went on to write about the murder trials of war criminals, the chaos of Berlin as people from the east and freed prisoners of war tried to gain entry to the British sector, and the long-term fate of the thousands of refugees and evacuated civilians in the heartlands of shattered Europe. A memorable positive experience was when she joined the return voyage of the Norwegian government from exile and was in Oslo to greet King Haakon’s arrival.

Her by-line was sought after by U.S. editors and she was commended for the thoroughness and range of her war reports by AP’s U.S. bureau chief, Alan Gould. Considered fearless and formidable by most people who knew her, she nevertheless recalled in a recent interview, ‘It was all very, very frightening. Anybody with any sense was frightened. For the military personnel and politicians the main concern – the justification for the D-Day invasion – was to liberate occupied Europe. But in Normandy in the summer of 1944, what concerned me was the effects on the civilians – how they coped, the consequences to their lives. It’s impossible for people to think about the bigger picture when day-to-day survival is the main issue.’

The survival of traditional communities became one of her life interests. She worked in the U.S. for Kemsley Newspapers and, in 1948, began her career as a professional traveller by writing for the Readers’ Digest about her 14,000 mile Greyhound bus journey, the first of many stories, later becoming a picture researcher for the magazine. Back in Fleet Street, she was one of the first women to make a success of freelancing after the war. She broadcast regularly for the then-new BBC World Service, and was on the spot to cover state events, such as Queen Elizabeth’s coronation, for the New York Times, then edited by E.C. Daniels who, with his wife Margaret Truman, became a lifelong friend.

Barbara enjoyed her independent life as a long-distance journalist – never, she insisted, ‘a travel writer’ – and worked in at least 60 countries. Her reports and photographs have appeared in most UK newspapers and magazines and international journals such as National Geographic. She filed her stories of people and societies from remote locations, often the first to report from former trouble spots or countries unknown to Western tourists, for instance Albania in 1957 with the first visitors in 20 years, Burma, Malagasy, Madagascar and the Philippines. At her own suggestion she toured the Middle East, including North Yemen, Oman, Muscat and the Emirates, during the years of rapid urban modernization as the oil industry boomed, teaming up with surveyors and dining with desert communities.

Barbara enjoyed her independent life as a long-distance journalist – never, she insisted, ‘a travel writer’ – and worked in at least 60 countries. Her reports and photographs have appeared in most UK newspapers and magazines and international journals such as National Geographic. She filed her stories of people and societies from remote locations, often the first to report from former trouble spots or countries unknown to Western tourists, for instance Albania in 1957 with the first visitors in 20 years, Burma, Malagasy, Madagascar and the Philippines. At her own suggestion she toured the Middle East, including North Yemen, Oman, Muscat and the Emirates, during the years of rapid urban modernization as the oil industry boomed, teaming up with surveyors and dining with desert communities.

Planning to tour re-built Europe, she converted an old Post Office van which, unfortunately, was retired to the Pett Level marshes in Sussex after it broke down outside Margot Fonteyn’s house in Taplow on the Thames. Fonteyn, a cousin by marriage, later invited her to Panama to write on her life after the assassination attempt on her husband, the politician Roberto Arias.

Barbara was renowned for creating her own style of ambassadorial journalism. She had a talent – described by a one colleague as an ‘almost magic capacity’ – for making friends of all ages and all types wherever she went, and for merging them successfully at her parties. She became a fund of information for younger writers, especially adventurers and voyagers (such as Tim Severin) helping them to negotiate diplomatic barriers. Inevitably, her tiny 5th floor Fleet Street flat was a magnet for visitors as well as press colleagues and offered a birds’ eye view of demonstrations, State funerals (including the eerie dawn rehearsals) and the annual Lord Mayor’s Show. Major U.S. figures of the war years, returned explorers or stranded MPs (and once a spy) often shared floor space with relatives, friends’ children, homeless teenagers or celebrities incognito.

In her farewell feature on the Street’s long literary history (Daily Telegraph, 14 Sept 1985) she recalled that she’d lived there originally solely because, during the Blitz, she was unable to find late-night transport after shift work. She took a flat in Old Mitre Court above the Clachan pub, moving 20 years later when it was demolished for rebuilding to her legendary attic at Number 53, opposite the Picture Post building. She immortalised the characters who had created the village-like atmosphere, including the postman who had daily climbed the 96 steps with her stacks of mail. Herself a talented pianist, she found time to support popular culture. She loved children, often taking large groups to theatres and offbeat events. She promoted artists from abroad and young British performers (such as Hamish McColl).

Barbara is survived by her younger sister, Daphne, nieces and nephews in the UK, Canada and the U.S.A. and their families, and also will be mourned by scores of friends and contacts worldwide.

Supplied by Valentine Fallan, with thanks to James Buchan and Anne Sebba. (et al.)

Further Reading

Article in The Independent: The story they didn’t want women to tell by Anne Sebba, 1st June 1994

Obituaries

Obituary in The Independent by James Buchan, 30th January 2003

Obituary in The Times, 22nd January 2003

Obituary in The Telegraph, 21st January 2003