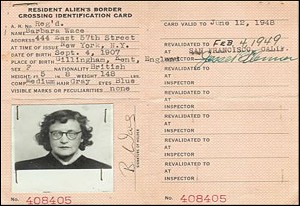

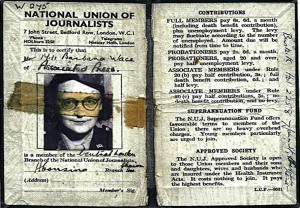

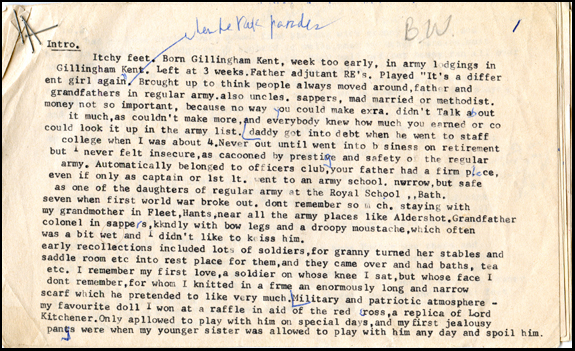

Childhood memories by Barbara Wace

These notes (and they are only notes) by Barbara on her childhood were kindly passed on to me by Val Fallan and Sarah Hamilton. I have transcribed them as accurately as possible, including any handwritten amendments where I could read them.

Intro.

1.

Itchy feet. Born Gillingham Kent, week too early, in army lodgings in Gillingham Kent. Left at 3 weeks. Father adjutant RE’s. Played “It’s a different girl again”. Brought up to think people always moved around, father and grandfathers in regular army. Also uncles. Sappers, mad married or Methodist. Money not so important, because n o way you could make extra. Didn’t talk about it much, as couldn’t make more, and everyone knew how much you earned or could look it up in the army list.

Itchy feet. Born Gillingham Kent, week too early, in army lodgings in Gillingham Kent. Left at 3 weeks. Father adjutant RE’s. Played “It’s a different girl again”. Brought up to think people always moved around, father and grandfathers in regular army. Also uncles. Sappers, mad married or Methodist. Money not so important, because n o way you could make extra. Didn’t talk about it much, as couldn’t make more, and everyone knew how much you earned or could look it up in the army list.

Daddy got into debt when he went to staff college when I was about 4. Never out until went into business on retirement but never felt insecure, as cocooned by prestige and safety of the regular army. Automatically belonged to the officers club, your father had a firm place, even if only as captain or 1st Lt. Went to an army school. Narrow but safe as one of the daughters of regular army at the Royal School, Bath. Seven when first world war broke out. Don’t remember so much. Staying with my grandmother in Fleet, Hants, near all the army places like Aldershot. Grandfather was a bit wet and I didn’t like to kiss him.

Early recollections included lots if soldiers, for granny turned her stables and saddle room etc into rest lace for them, and they came over and had baths, tea etc. I remember my first love, a soldier on whose knee I sat, but whose face I don’t remember, for whom I knitted in a frame an enormously long and narrow scarf which he pretended to like very much.

Military and patriotic atmosphere – my favourite doll I won at a raffle in aid of the red cross, a replica of Lord Kitchener. Only allowed to play with him on special days, and my first jealousy pangs were when my younger sister was allowed to play with him any day and spoil him.

2.

Mother had no home during war, moved from staying with granny at Fleet, and being innumerable lodgings in Tunbridge Wells, near my other grandparents. Must have been very trying for her, as Granny Sim, kind, well off, but bossy, ran all over her, and Granny Wace impossibly tiny, V.V. evangelical, and remember with agony the embarrassment when she made my handsome old grandfather, a sapper general retired, carry her harmonium out onto T. Wells common, where she played and we sang, “moody and sankey” hymns. Also first time I realized life was unfair. My brother Dick, red faced and shy. his voice hardly heard, while Reg, my cousin, looking saintly sang in a loud treble, words where were, to me, absolutely terribly rude (while shepherds washed their socks by night!). But Granny was fooled, she asked Dick why he didn’t sing like dear Reg, and God did not strike Reg dead.

I remember the lodging houses in T. Wells, in all of which there seemed to be a grumpy landlady, and from all of which we seemed to be turned out. Several times I remember sheltering in the Kardoma Café in the Pantiles, being sick – I was often sick, with emotion, with fear, with excitement, while mother still looked round for a place for her unruly brood to stay and where we were so often kicked out because we made too much noise.

I remember feeling no lack of sense of place or home, Mother was there, and that’s what mattered and anyway, Dick and I were convinced there were secret passages and priest holes in the newly jerry built villas we stayed in and used to press the wall all over to try and find the secret doors. At Granny Sim’s nice house in Fleet too, we looked for secret passages, and, put our feet through the ceiling of the spare bedroom in doing so, to Granny’s fury and poor mother’s embarrassment.

3.

An army childhood continues with going to France in leave boat with dad, who spent his time avoiding a drunken sergeant as he didn’t want to discipline him. Wimereaux, where Dad was head of the Labour Corps and I played on the beach with the Chinese labour corps, who taught me how to fly kites and I learned the pride of beating my brother by being able to climb Boulogne Cathedral alone with the guide, while he, having vertigo like my mother, had to stop at the first tier.

There were even a few memories before the war. The green baize door, for instance, which divided the family’s part of the house in Fleet from the servants quarters, and which at age of 4 (check), I remember the cook saying that Edward VI had died, and the German governess my father hired so we could be looked after and he bone up for his interpreter’s exam, saying in guttural tones “and everybody loffed him so”. Sense of occasion. Perhaps birth of news sense. I remember living at Sandhurst, near Camberly, too, when dad was at the staff college on money borrowed from cousin Cyril, and playing endless games of gypsies with Phyllis my elder sister and Dick, and the agony of always being the baby the gypsies stole, carried with difficulty by my brother, only 3 years older, and always dropped with a bump, when we got to the gypsy camp at the corner of the garden, Seemed huge to me, but I went back once and it was tiny. Don’t remember the was ending, but remember the news coming of my sapper uncle Ted’s wound – he lost his arm. I was lying on a sofa in one of the lodgings, and mother was dressing – I remember she was putting on her Spirella Stays when the telegram came, and tears at contents. That garment always associated for me with sadness. Uncle Ted my first hero.

4.

After the war my father made president of the border commission, of the Saar. I was at a small dames school at Tunbridge Wells, Miss Worcester’s, and boarded while my parents and Daphne, the baby, settled in Saarbrucken. Then joined them for a couple of terms, and have vivid memories there. First the journey, with Dick. He was aged I suppose about 12, and me about 9. I have always had my emotions seated in my stomach, so I used to be sick all along the way. Train to Dover, or, crossing to Oostende. Once I was so sick that I strained my heart, and that time my brother had difficulty getting me onto the train to Brussels. I lost my hat in the process, and got into great trouble. When in Brussels I learned to admire my brother even more than before. We stayed in what seemed to us a luxurious hotel and he went out into the strange city by himself, leaving me in the room where I failed to sleep as I couldn’t find the switches to put out all the lights we’d put on in our first exuberance, I wonder what he did – had an innocent coffee I expect, but I imagined all sorts of brave and fearsome episodes in the evil city. Very shy, had problems on the journey. Once we had to take out lots of Ovaltine for Daphne, who was then quite small. When the customs saw it they believed it, I think, to be some sort of gunpowder. Red in the face, and stolid, my brother kept repeating in atrocious French “lait” “lait”. In despair they let us through.

After the war my father made president of the border commission, of the Saar. I was at a small dames school at Tunbridge Wells, Miss Worcester’s, and boarded while my parents and Daphne, the baby, settled in Saarbrucken. Then joined them for a couple of terms, and have vivid memories there. First the journey, with Dick. He was aged I suppose about 12, and me about 9. I have always had my emotions seated in my stomach, so I used to be sick all along the way. Train to Dover, or, crossing to Oostende. Once I was so sick that I strained my heart, and that time my brother had difficulty getting me onto the train to Brussels. I lost my hat in the process, and got into great trouble. When in Brussels I learned to admire my brother even more than before. We stayed in what seemed to us a luxurious hotel and he went out into the strange city by himself, leaving me in the room where I failed to sleep as I couldn’t find the switches to put out all the lights we’d put on in our first exuberance, I wonder what he did – had an innocent coffee I expect, but I imagined all sorts of brave and fearsome episodes in the evil city. Very shy, had problems on the journey. Once we had to take out lots of Ovaltine for Daphne, who was then quite small. When the customs saw it they believed it, I think, to be some sort of gunpowder. Red in the face, and stolid, my brother kept repeating in atrocious French “lait” “lait”. In despair they let us through.

In Saarbruken we were, if I remember right, billeted first in the Hotel Messmer, again which seemed very grand to us. None of us except Dad spoke German, and I remember mother having difficulty with the menus. The most suitable food for children turned out to be “remoulade eier”, hard boiled eggs in mayonnaise, and belegte brodchen, open sandwiches. All a bit binding. My elder sister, Phyllis, in her late teens, gathered a silent admirer, I can’t remember whether French civilian, or German. Anyway, he stood outside the hotel for hours looking at our windows – we had a suite – and it seemed immensely exciting.

5.

I spent one term in Saarbruken, going to a French school which used a German school for part of the day, the afternoon I think. Since I spoke no German and not much French, I went to all the German writing lessons, which had an appalling effect on my handwriting which was just being firmed with English un-joined script. Anyway, it’s been a good excuse, as the German schrift was quite different. I also went to French spelling classes, and dicté, at which I was no good. I must have been rather objectionable, as I distinctly remember spending one intermission between classes drawing Union Jacks on the blackboards of every classroom. Altogether, I think, having been a regular soldier’s daughter in wartime, I was rather blatantly patriotic. One of my earliest recollections is standing on my bed, balancing as still as I could with my toes turned into the sheets, and my hand in a salute as we finished prayers or Sunday hymns with God Save the King.

Saarbrucken I remember as a crowded, dark city, with frequent fracas and riots, and police who were frightening as I think they carried swords. We didn’t go out much alone, except when Daphne got diphtheria, and my poor mother was incarcerated with her in the army hospital, with nurses who only talked French, only used a French thermometer she couldn’t read, and frequently “cupped” her with heated glass bubbles for her asthma to which she was a martyr during the hay fever season. She couldn’t understand what the doctor said. her French was minimal, and when she was fussed she reverted to Hindustani she’d learned as a young bride in India. We used to go and cheer her up, Phyllis and I, by talking through the window, Dad seemed always to be away working on his Commission de délimitation de la Sarre of which he was president.

6.

After some time we all moved into a private house where we were billeted on two old ladies, who if I remember right, were elegant, proud, and very resentful at our being there though superficially “correct”. They dressed in black, with high whalebone collars and I can’t remember their names. They always, so my parents were convinced, turned off the hot water at anybody’s bath time. An understandable way of revenge.

We didn’t eat there, except perhaps breakfast, but had a “mess” for the commission members, except of course the German member who I never even met. There was a Frenchman called Laurent, with a very voluble wife from the Midi, a rather pretty teenage daughter called Miriam whom I liked and a perfectly audacious little son about my age – 12. He was spoiled, fat, whiney and I battled with him continually. His name was Serge. There was also a very pretty typist, or dactilo, called Yvonne, blonde, cute and coy, with a mother for chaperone. We concluded she, the daughter, was also Col Laurent’s mistress. (Check with Daphne if she was Laurent’s mistress or the mistress of the Japanese Colonel Kobayishi, which on second thoughts I think is right.)

Kobayishi I remember as a charming, squat little man, with I believe a wife and son in Japan. He was very nice to Daphne and me, and it was on his knee that I learned to like “petit canard” – French beet sugar lump dipped in brandy. I’ve like d it ever since. (Check with Daphne on other members if the commission.)

Meals were served by a mess cook, German, and his wife, who did quite well, but was a bit overcome by our traditional Christmas dinner to which we invited a lot of French and other guests. He managed the turkey magnificently, and the stuffing, for mother, a typical army wife, was a hopeless coo, but what foxed him completely was the bread sauce. He made an enormous pudding basin full of it, serving it as a separate course, to the bewilderment of our guests and mother’s embarrassment.

7.

Phyllis had a wonderful time in Saarbrucken, for she was vivacious and the toast of the garrison (French). We had some very good French friends who stuck after we left. One admirer was Bernard de Perhimouff (Daphne how do you spell?), who owned mines there, and whose family were rich. He was in love with Phyllis was always told, and she kept up with them afterwards. After the war I looked them up, found that his family’s house in the Avenue Foch in Paris had been headquarters for the German Gestapo, that some of the family had been strong in the resistance, Bernard I fear, not, for when I had a party in the Scribe Hotel and invited everybody I knew, some of my French friends pointed at him and asked why I had invited such a colaborateur (” Le plus grand colaborateur de monde”), though I believe his wife was a Resistance Leader

I remember Poline, a nice gentle Frenchman from near Nice, a very offensive supercilious Frenchman named Pajot, who loved to make my mother say things wrong in French like “je suis tres excité” etc, and a General Bruissaud DeSmailler and his family. PomPom was another of Phyllis’ boyfriends, a very good family, a major from a crack Alpine regiment, de Pontavice. And a tall handsome rider called Braux, who won all the concours hippique, and who had, I remember a double set of natural teeth, or so I believed, I think I had a picture somewhere. I can’t remember falling in love in Saarbrucken, which is surprising as I was very impressionable and violently in love with Charlie James whom we met at an unusual holiday in Aldburgh, and who delighted me by asking my father if he could dance with his daughter at a village hop. I must have been about 11. He turned up again in London just after the war, a well known dress designed from Chicago. He must have read my by-line in America, for he asked that I should be invited as the AP representative at his dress show, and when I saw him again, declared he remembered my other as the only person who ever gave enough shrimps for tea – not a bad thing to be famous for! Daphne though, who must have been only about 7, had a “young man in brown” whose name we never got, but about whom she was terribly teased.

8.

I don’t know how successful the commission was – I once met somebody who said my father was responsible for the second world war because of it, which I can’t think is true. But socially we all had a lot of fun and I’m sure Dad helped along the Anglo French relations. I remember one tremendous party, I think a New Year’s eve one, where we taught the assembled international guests to do a tremendously energetic mixture of Sir Roger de Coverly and the Swedish Dance which they immediately dubbed “le jig”. It was fun and exhausting and everybody joined in from Generals to dactelos, and of course children.

Brazilian, De Castro, check with Daphne if it was his secretary. Daddy’s commission wound up, I think, in Paris, where I only went for the holidays, being safely immured in Miss Worcester’s school in Tunbridge Wells in term time. I never have felt I’ve been lucky in Paris, for an infection laid me up most of the holidays, and I only recall a rather abortive evening “treat” with Daddy and Phyllis, where seats had been booked for a safe musical comedy. When we got there, however, the theatre was closed unexpectedly because of the death of the owner or chief actor, and Phyllis and Dad got into hot water by taking me across the street to the Casino de Paris, which shocked my mother terribly because of the naked ladies. All I remember was the quite marvellous settings and music and props like enormous fans, and Phyllis insisting, rather nervously, that I mustn’t mind the girls with no clothes on as it was “only what you see in your bath”! Mistinguett was the female lead, and I can remember her charm – I interviewed her after the war when Maurice Chevalier was under fire for collaborating by singing for the Germans in French prisoner of war camps. She laughed off any political affiliation for her ex-partner by insisting he was just “a silly boy”, with no politics, which I think was about right, and I hope I gave him a bit of a lift when he was down in 1946. I don’t remember much more about Paris since I was ill, but we did a bit of sightseeing and I had my first and only cigarette with our French maid Augustine when the family was out and she was free to snitch a family cigarette. She came to England with us for a while, and was very pretty, and had a boy friend at a local store who we dubbed “le jeune homme chez Weeks” and who I only knew about for a time.

9.

The things one remembers from childhood are so diverse, it is often hard to imagine why each episode has stuck. For instance, I remember having elevenses at the Tudor or the Kardomah Café in the pantiles of Tunbridge Wells, and for some reason the clock which hung outside was on the ground, being mended or cleaned, I suppose. I touched it, and Dick said “You’ll always be able to remember you touched the dace of that clock when it is up again” and I always have, even at my great age, with a certain amount of pride. And I remember the embarrassment, when Daphne, much the youngest in the school, went for a walk with the whole assembly and, because somebody had snitched her suspender belt, had to be taken home by me in front of everybody as her brown stocking concertinaed down her ankles. I remember, to me shame, being absolutely horrid to her about it. Not kind at all.

10.

I remember another humiliating moment when, eager to win favour, as I was a bit of an “apple polisher” I jumped down from the dining table where I sat next to old Miss Worcester the head, to pick up what she had dropped – discovering to my horror it was a whole set of false teeth, I did have the tact though to pass them back to her under the table, and neither of us ever mentioned the episode when we talked.

Another memory is of going for a walk with Daddy, dressed, I remember in his uniform, and receiving a terrible lecture about the evils of borrowing money. I had borrowed half a crown from Joyce Whicker and not paid it back. It made such an impression on me that I don’t have any charge accounts at all, and only recently weakened to obtain a bankers card. I imagine my Dad spoke with feeling as he had a borrow from cousin Cyril, the Dean’s doctor’s son, to go to the staff college, and I believe wasn’t able to pay it all back until he went into business on leaving the army as a Brigadier General and even then was overdrawn pretty constantly and had to borrow on his insurance, something which worried him terribly in case he died before mother. But I guess the lecture was a good thing really. I’ve never saved money, and look like getting to debt now in my old age, which is quite a long time to wait.

Horribly, I remember Granny Sim packing my trunk and herding me into a taxi when I was being incredibly naughty when my mother was coping with Daphne, a small toddler, and Phyllis, with an acute eye infection. “I’ll take her to the school to board, and give you some peace”, she declared, and there I remained relatively happy until I graduated to the Royal School at 13. But the public humiliation was immense, for the trunk, a brown steamer one, crammed full, burst open as it was carried up the steps, and horror of horrors, the packets of sanitary towels which it was to be many many months before they became necessary, hurtled out for all to see. (pupils glued to windows watching me arrive.)

I remember the lessons at Thornleigh very little. Just music which I loved, and history and English> And the pleasure of being rather good at French. I don’t think the teaching was terribly good, but I think they taught me to want to read, and I know I was happy there.

11.

Intro might go on to describe visits with Dad when he was at Aldershot and very ill. And hearing at the Royal School that I didn’t have to leave which was on the cards when he got thrombosis and other complications after being hit with a cricket ball. It was a blow for him, not only financially, as he’d not been “with troops” in a garrison for years and was looking forward to it. We lived in Farnborough Hants in Reading Road, and had a horse (daddy’s charger) and a trap and a soldier servant batman in the cottage called Selby. We went to parties in the trap, or later I rode a bicycle beside it, and I remember the troops down royal avenue Aldershot shouting “nice legs darling” when I went past and being rather pleased, though was shy at that age. Phyllis was again, the toast of Aldershot with lots of boyfriends, and I was scared at them, and preferred to ride down royal avenue than to go into tea and meet them at tennis parties. I remember though, one of the very few times my mother really balled me out. I had to go to a teenage party and said I was shy and didn’t want to go.

“I’m shy I grumbled”. “You can’t afford to be shy,” said my mother tartly. “People in the army have to put down their roots wherever they are quickly, or you’ll have no friends.” It was good advice and has stood me in good stead. Another time, when I said I didn’t know how to make conversation to strangers, she said sharply, “Don’t imagine people invite you to parties because you’re beautiful, or for your pretty face. They invite you to make the party go.”

12.

That was good advice too for the life I’ve led, and I’m grateful. I often think I get the chance to go on press trips even at this late age because I’m pleasant and talk to boring mayors and hotel managers politely and don’t get drunk! Negative virtues, but responsible for getting me round the world, as I explained to my mother when she was old and afraid she was holding me back. I hope it cheered her up. Just being pleasant is a useful thing to learn.

She was infinitely kind and loving and pleasant, but she didn’t encourage me to be vain. I remember the agony of having to go to a fancy dress teenage party as a “Dresden china shepherdess” – the dress had been lent and was exquisite, but I felt awful as I was fairly fat and lumpy and was sure everybody would laugh at the idea of my being Dresden china. I remember hating one hat she bought me so much I “lost” it at the back of the drawer and when it was discovered, it had been ruined. And I remember my pang of awful, really awful jealousy, when Daphne had a summer coat bought specially for her. I always had Phyllis’ reach me downs, or worse, those which had belonged to “the Parringdons”, boring elder cousins, clergy daughters, with terrible taste, Never never did I have anything new. I still feel hot and angry when I think of Daphne’s coat, which wasn’t really fair, as more often than not she had to wear clothes not just second but third or even fourth hand.