Putting Your Foot In It

Some things in life are constant. As babies we grow into childhood, dependant on certain things not changing.

Gravity. Temperature. Sky. Time. Day. Night.

We learn from the environment we inhabit, and how to interpret it, allowing us to do all the things that will later in life become instinctive. How to reach out for food and bring it to your mouth. How to sit down, controlling your descent just enough for gravity to do the hard work. How to check that something isn’t too hot to touch.

And where to put your feet as you walk.

A puddle will lead to wet feet. Gravel will be sharp. Coarse grass will cut. Dark tarmac will burn. Morning dew is cold, no matter how sunny it is.

I grew up in a variety of environments and landscapes, and was lucky enough to be able to spend much of my childhood without shoes on. And when you are barefoot you learn quickly how to effectively navigate through your environment. You are constantly scanning the ground ahead, subconsciously avoiding discomfort and danger. Mistakes lead to pain.

This innate knowledge has served me well when taking photographs. I can skip (in my mind) from possible image to possible image while my feet skip daintily (I wish) from hillock to mound to rock, keeping me safe from harm, embarrassment (you never know who is watching), puddles and marshes.

Yet despite this deep seated, instinctive knowledge that everything will be as it should, the world we live in can still spring the occasional surprise – both delightfully unexpected and gleefully nasty.

In the northwest of Scotland should you wish to stray from the path you will be confronted with bogs and marshes – water, peat and plenty of general wetness.Yes, there are scattered mounds covered in heather and other vaguely familiar plants, but between these hillocks are many puddles and streams. In theory, navigating your way around them should be easy – just step from mound to mound. Gravity and logic will ensure that any wetness and bog is below the top of the mound…surely?

My first five (dainty) leaps and bounds were perfect.

The sixth, I slightly misjudged and my foot landed towards the bottom of a mound. I expected to sink, but I didn’t. It was dry – a minor miracle. Filled with confidence I continued.

Seven, eight, nine and ten. Flying through the world.

Then eleven.

A perfect landing, bang in the centre of a mound a foot high, covered in shrubs…yet my boot kept going, down, down into the depths of the earth. Ankle deep, then knee deep. Soaked, water seeping through everything. And stuck – suction stuck. Balanced precariously, camera in hand I squelched and levered myself out as quickly as I could, feeling confused and betrayed by nature.

How could this be? What manner of witchcraft conspires to make the top of a mound wetter than the bottom? Had nature deserted me? Will I now miraculously and suddenly be able to fly like a bird? Walk up walls? Where were the constants of the world when you needed them?

Three days of sporting a brown, crusty leg followed, and no new ability to defy the laws of nature manifested themselves. The gleeful, sadistic and yet wonderful humour of nature displayed on my legs for all to see.

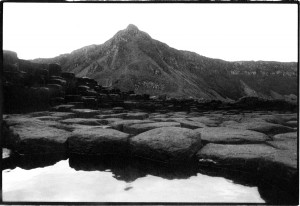

Fast forward two months and I was in the centre of Iceland – and what a country; bursting, popping and fizzing with the unexpected and surreal.

Once again it was moist, the air dripping from my nose. The rocks and stones – a sharp volcanic black – had a slippery sheen to them. As I ventured further from the road, the ground gradually disappeared under a moss I had never seen before. It was a light gunmetal grey with just a hint of dusky green coming through – thick, absorbent and bouncy. It was the sort of thing I expected to see growing from the horns of a reindeer, stood over you as you wake from a dream.

And it was an absolute delight to walk on.

Despite knowing that my feet would be soaked through in a matter of minutes, I bounced towards the patches of snow I was aiming for, relishing this new experience for my faithful feet.

Several photographs later I slowly became aware of something pulling at the corners of my mind – reality was calling me back and it wasn’t happy.

“Your feet are still dry” it said. “How?” it asked. “Why?” it wondered.

My boots are several years old, and while they still do their job extremely well, they are by no means completely waterproof. So i did something my curiosity should have made me do when I first saw the moss: I reached down and touched it…

Such an overwhelming experience for my senses…it was so soft, so tactile, and so…dry.

I looked up (yes, it was still raining).

I looked down (yes, my hands were dry).

I could not compute. Falling rain, dry ground?

I felt reality grin. It felt smug, justified about calling me back.

The moss made me want to lie down and sleep in it. Should I? Would I wake up in thirty years with a long, grey beard, surrounded by the infamous little people of Iceland? Was it them? Just out of the corner of my eye, using their magic to keep their bedding dry? Watching me lumber past, huge and ungainly?

Once again nature was toying with me.

Only this time it was her delightful, unexpectedly surreal humour in full view, not her gleefully sadistic side.

And I loved it, loved her, loved life, loved Iceland and definitely loved her little people for keeping my feet dry.

An unconditional love.